distinct for all people, including colour-blind readers.Is handy to have a palette of colours that are: To make graphics with your scientific results as clear as possible, it Paul Tol provides a colour scheme optimised for colour differences (i.e., categorical or qualitative data) and colour-blind vision on his website, and in detail in a "technote" (PDF file) linked to there.

Small multiples can be better for several groups than a multicolour plot. Using seven colours for seven groups in principle carries the information, but it's hard even to focus on one colour at a time when there is competition from several others. If one group is of particular interest among several, make it blue or orange, and let the others be grey. If two groups are both of interest, then choose equally strong colours (e.g. A fairly general principle is that often two colours work much better than many. (It is a lousy printer that can't make a fair bash at grayscale.) (Grey if you like preferences change across oceans, it seems just as with colour and color.) Grayscale from pale gray to dark gray can work well and is a good idea when colour reproduction is out of the question. Many introductory books on visualization now recommend orange, blue and grey as a basic palette: orange and/or blue for what you care about and grey for backdrop.

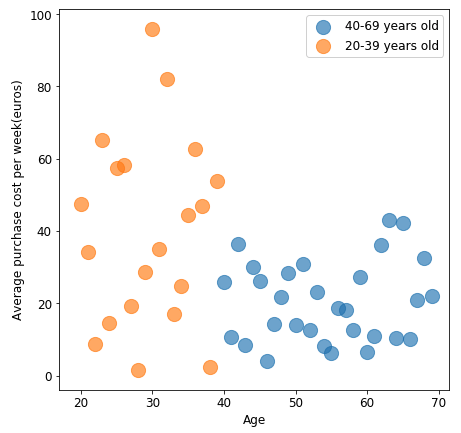

Two different colors bubble scatter plot matplotlib Patch#

White can make sense for bar colours if there is a boundary (say in a light gray) to the patch showing where the bar ends! (ditto, area patches on maps)īlue and orange go well together (a grateful nod to Hastie, Tibshirani and Friedman here. Too obvious to underline, but I do it any way: Red and blue do have political connotations in many countries. Perhaps too obvious to underline: red has connotations of negative and/or danger for many, which can be helpful, and blue can then mean positive. If white is (as usual) the background colour anywhere, don't use it, but skip from pale red to pale blue. For example, yellow is usually a weak colour while orange and green are usually stronger, so the impression is not even of a monotonic sequence.Īvoid any colour scheme which has the consequence of large patches of strong colour.Ī sequence from dark red to dark blue works well when an ordered sequence is needed. Rainbow sequences (ROYGBIV or red-orange-yellow-green-blue-indigo-violet) may appeal on physical grounds, but they don't work well in practice. Never rely on a contrast between red and green, as so many people struggle to distinguish these colours. (If your pie chart depends on a key or legend, you are likely to be trying the wrong kind of graph.) For a pie chart with text labelling on or by the slices, colour conveys no extra information, for example. Beware fruit salad or technicolor dreamcoat effects. For other kinds of graphs, colours may be dispensable or even a nuisance.Īre your colours all needed? For example, if different variables or groups are clearly distinguished by text labels in different regions of a graph, then separate colours too would often be overkill. For a choropleth or patch map, in which the idea is indeed that different areas are coloured or at least shaded differently, the success of a graph is bound up with the success of its colour scheme. This is all just advice, naturally, to be thought about given the key questions: What is my graph intended to do? What makes sense with these data? Who are the readership? What I am expecting colour(s) to do within the graph? Does the graph work well, regardless of someone else's dogmas?įurthermore, the importance of colour varies enormously from one graph to another.

Much outstandingly good advice in other answers, but here are some extra points from my own low-level advice to students.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)